Despite the setback from the pandemic, the predicted growth rates for the three most prominent nations in Asia, China, India and Indonesia, remain positive.

The Covid-19 pandemic has significantly impacted the Asian market, and the construction industry was one of the hardest-hit. The sector faced a massive shortage of labour, long lockdown periods, a surge in raw materials prices, a cost increase due to pandemic prevention, and difficulties in adhering to the project schedule.

Nevertheless, the sector has shown remarkable resilience during the worst of the coronavirus pandemic. This resilience is due in large part to efforts by the governments implementing a series of initiatives to aid industry players during the time of crisis, including stimulus efforts and mass vaccinations.

China

As the pandemic’s first global epicentre, China’s construction SPECIAL FEATURE 2 3 Leishenshan Hospital at Wuhan sector experienced its weakest growth in 30 years, expanding by just over 1% The Chinese construction sector is mainly reliant on rural migrant labourers who returned to their hometowns for the lunar new year celebrations and cannot return to work sites following the lockdown in early 2020. More than 54 million people were affected, and progress on construction projects was severely hampered.

Nevertheless, in less than two weeks, China accomplished an astounding construction feat in February 2020 by constructing two facilities in the pandemic’s core, Wuhan, to isolate and treat COVID-19 patients. The two-storey buildings, mostly made of prefabricated rooms and components, were called “instant hospitals.” On 3 February, the 1,000- bed Huoshenshan Hospital (meaning Fire God Mountain) opened its doors. Five days later, a sister hospital, Leishenshan (which means Thunder God Mountain), opened with an additional 1,500 beds. They were officially closed on 15 April 2020 due to the nation’s successful efforts to combat Covid-19.

Significant government stimulus efforts in China, mainly focused on infrastructure, have seen construction activity rebound in 2021 and will support efforts in 2022.

These efforts include the Chinese government granting requests for extensions of time (EOT) to project completion dates. The government made a conscious effort to strike a balance between the employer and the contractor, with each party sharing losses, liabilities, and costs ensuing from the pandemic.

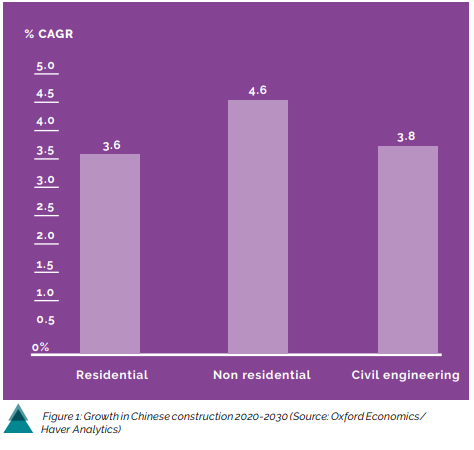

But over the medium-term, as forecast by Oxford Economics in the ‘Future of Construction – A Global Forecast for Construction to 2030’ report, less emphasis will be placed on infrastructure projects, and more attention will be placed on developing non-residential real estate investment.

The government has signalled that infrastructure spending is less important by issuing fewer local government special bonds for infrastructure spending. This is part of a broader movement in China’s economy, as the country shifts away from its former growth model, which emphasized heavy industry, infrastructure and investment, and toward consumer-led growth. This will result in additional construction in the non-residential sector, such as retail, entertainment, health, and education buildings. The relatively high vacancy rates in Chinese office and business space, on the other hand, will put a damper on new commercial buildings.

Residential construction in China is expected to continue to be essential. But there won’t be a repeat of the incredible surge in new homebuilding that supported China’s population urbanisation. However, there will be a substantial amount of renovation and maintenance work to perform to support the mass of housing blocks erected across China over the past 20 years, often to poor building standards.

China’s growth would progressively decrease in the long run as the country’s economic status matures. The double-digit growth surge in construction seen in the 2000s will not be repeated. However, there will be construction opportunities in some of China’s emerging first-tier cities and special economic zones that will maintain construction growth. Over the next five years, Oxford Economics Forecast construction to grow 3% to 5%.

In June 2020, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that 30%–40% of Belt Road Initiative (BRI) projects were impacted by the pandemic, while a further 20% had been seriously affected. According to numerous media outlets, during 2020, several BRI projects were paused to allow countries affected to focus on the spread of the pandemic. In recent months, a number of these projects have been restarted.

China

As the pandemic’s first global epicentre, China’s construction SPECIAL FEATURE 2 3 Leishenshan Hospital at Wuhan sector experienced its weakest growth in 30 years, expanding by just over 1% The Chinese construction sector is mainly reliant on rural migrant labourers who returned to their hometowns for the lunar new year celebrations and cannot return to work sites following the lockdown in early 2020. More than 54 million people were affected, and progress on construction projects was severely hampered.

Nevertheless, in less than two weeks, China accomplished an astounding construction feat in February 2020 by constructing two facilities in the pandemic’s core, Wuhan, to isolate and treat COVID-19 patients. The two-storey buildings, mostly made of prefabricated rooms and components, were called “instant hospitals.” On 3 February, the 1,000- bed Huoshenshan Hospital (meaning Fire God Mountain) opened its doors. Five days later, a sister hospital, Leishenshan (which means Thunder God Mountain), opened with an additional 1,500 beds. They were officially closed on 15 April 2020 due to the nation’s successful efforts to combat Covid-19.

Significant government stimulus efforts in China, mainly focused on infrastructure, have seen construction activity rebound in 2021 and will support efforts in 2022.

These efforts include the Chinese government granting requests for extensions of time (EOT) to project completion dates. The government made a conscious effort to strike a balance between the employer and the contractor, with each party sharing losses, liabilities, and costs ensuing from the pandemic.

But over the medium-term, as forecast by Oxford Economics in the ‘Future of Construction – A Global Forecast for Construction to 2030’ report, less emphasis will be placed on infrastructure projects, and more attention will be placed on developing non-residential real estate investment.

The government has signalled that infrastructure spending is less important by issuing fewer local government special bonds for infrastructure spending. This is part of a broader movement in China’s economy, as the country shifts away from its former growth model, which emphasized heavy industry, infrastructure and investment, and toward consumer-led growth. This will result in additional construction in the non-residential sector, such as retail, entertainment, health, and education buildings. The relatively high vacancy rates in Chinese office and business space, on the other hand, will put a damper on new commercial buildings.

Residential construction in China is expected to continue to be essential. But there won’t be a repeat of the incredible surge in new homebuilding that supported China’s population urbanisation. However, there will be a substantial amount of renovation and maintenance work to perform to support the mass of housing blocks erected across China over the past 20 years, often to poor building standards.

China’s growth would progressively decrease in the long run as the country’s economic status matures. The double-digit growth surge in construction seen in the 2000s will not be repeated. However, there will be construction opportunities in some of China’s emerging first-tier cities and special economic zones that will maintain construction growth. Over the next five years, Oxford Economics Forecast construction to grow 3% to 5%.

In June 2020, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that 30%–40% of Belt Road Initiative (BRI) projects were impacted by the pandemic, while a further 20% had been seriously affected. According to numerous media outlets, during 2020, several BRI projects were paused to allow countries affected to focus on the spread of the pandemic. In recent months, a number of these projects have been restarted.

India

According to India’s Construction Industry Development Council (CIDC), the pandemic caused the overall output of the construction industry to decrease by about 11%. This was mainly because the workers and other staff members have temporarily returned to their home cities.

The Indian government extended the time of completion for projects, and the pandemic impact was declared as force majeure.

Many rural infrastructures were built by returning workers in their local areas, aided by the Prime Minister’s housing and toilets scheme’s. The government’s welfare scheme for jobless rural employees has benefited more than 40 million workers.

The Indian construction industry is now returning to normalcy. CIDC observed that even during the pandemic, many major worksites in India experienced high productivity due to improved transportation and reduced political interference.

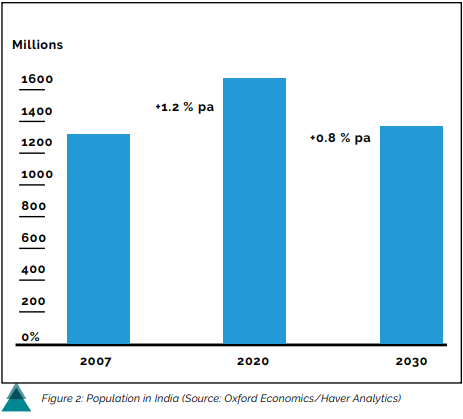

Oxford Economics reports that the industry will have two central drivers: demand for new homes and huge infrastructure needs over the next decade. The need for new infrastructure is directly tied to the country’s growth trajectory. As the Indian economy grows, the demand for new transportation infrastructure, electricity grids, and utility works will become increasingly important. Government land changes are seeking to make large-scale infrastructure projects easier to implement, but such reforms are proving tough to enact.

Strong population growth and the requirement for additional housing for India’s increasing urban middle class are driving demand for new homes. Strong urbanisation trends would fuel significant demand for new residential dwellings. At around 35%, India remains one of the world’s least urbanised countries. In comparison to China, population urbanisation was 35% in 2000; in the 20 years following, construction growth has averaged more than 10% each year.

It is tempting to compare India to China around 20 years ago, but such a comparison should be approached with caution. The decentralised nature of Indian democratic politics makes it far more difficult for a reforming government in Delhi to enact new changes, as evidenced with the GST bill and attempts at land reform. This was certainly not the situation in China, where a highly centralised, authoritarian government system made big reforms relatively straightforward to implement. As a result, Oxford Economics expects that Indian construction will increase at a rate of 7% to 8% per year, as compared to the double-digit growth experienced by China during its construction boom over the last 25 years.

Indonesia

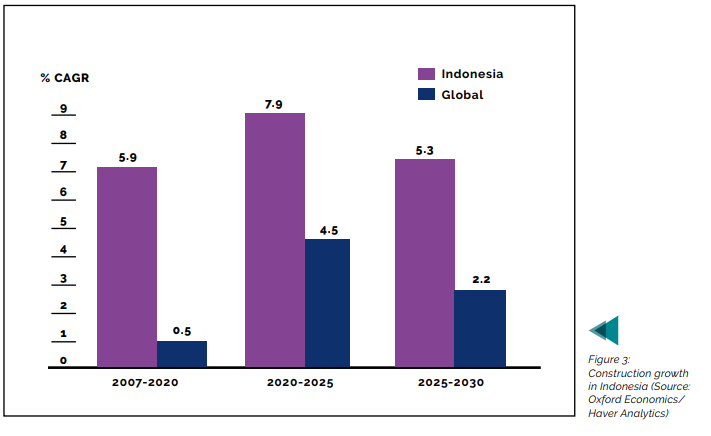

Indonesia accounts for over 40% of ASEAN’s economy and population, and investors are particularly drawn to the country’s robust economic growth and resiliency.

The construction industry has been viewed as the bedrock of Indonesia’s economic and social progress and is one of the country’s top 5 largest economic drivers. According to GlobalData’s Construction in Vietnam 2019 report, Indonesia’s construction sector grew at a 5.8% annual rate in 2019 and was predicted to continue growing through 2021 – 2024.

Unfortunately, due to the pandemic, it fell to 2.9% in Q1 2020, -5.39% in Q2 2020, and -5.67% in Q5, before registering its first 12-month positive growth at 4.42% in Q2 2021.

Fitch Solutions Country Risk and Industry Research reported that the Indonesian government initially earmarked nearly half of the 2021 budget to infrastructure development but was compelled to reallocate funding for healthcare. According to Fitch, the country’s construction recovery is “primarily dependent ” on government infrastructure expenditure.

Fitch also reported that more than half of construction contracts are allocated to Indonesian state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which are involved in most major infrastructure projects, such as the Patimban Deep-Sea Port in West Java and work on the Jakarta Mass Rapid Transit System.

In the midst of Indonesia’s infrastructure boom, these SOEs have amassed massive debts and are under increasing financial strain, resulting in delays and cash flow issues.

This has been hampered further by a spike in construction material prices throughout 2021, which Fitch expects to normalise by 2022.

Significantly, three years after the enactment of Law No. 2 of 2017 on Construction Services (Construction Law), the Indonesian government finally passed the Construction Law Implementing Regulations (Government Regulation No.22 of 2020 on Implementing Law No.2 of 2017 on Construction Services (GR 22/2020)), which took effect on 23 April 2020.

GR 22/2020 attempts to clarify certain aspects of the Construction Law, notably 12 specific issues listed in the Construction Law that will be governed further by their separate government regulations. These modifications cover, among other things, the construct of “Construction Services User,” limitations constructions business activities, construction services classifications and subclassifications, market segmentation, construction work contracts, and dispute resolution.

Indonesia’s construction outlook remains bright, buoyed by infrastructure projects and the recently announced new capital city in East Kalimantan. The plan to relocate the capital, which was supposed to begin in 2021, has been postponed until 2022 or 2023. The construction of a state palace, as well as upgrades to airports, harbours, and access roads, will be among the new capital projects postponed.

The Indonesian government approved a budget of IDR2.7 quadrillion (US$190.1 billion) for 2022 in September 2021, with IDR1.9 quadrillion (US$133.8 billion) allotted for central government spending and IDR770 trillion (US$54.2 billion) allocated for regional administration spending. Simultaneously, the government announced plans in the budget to allocate IDR384.8 trillion (US$27.1 billion) to the infrastructure sector.

According to GlobalData, the industry is predicted to increase at a 6.1 percent annual rate between 2022 and 2025, thanks to investments in the 2020-2024 National MediumTerm Development Plan (RPJMN). The government intends to create numerous transportation infrastructure projects as part of the plan to promote economic growth. During the period, the government intends to build 2,500 km of new toll roads, 3,000 km of new national roads, 38,726 km of bridges, and 31,053 km of flyovers and underpasses. The industry’s output over the forecast period will also be boosted by the Electricity Procurement Plan (RUPTL) 2021- 2030, under which the government expects to add 40.6GW of extra capacity by 2030, 4.7GW of which will be solar, and 51.6 percent of the capacity will be from renewable sources.

Continued investment growth, combined with healthy consumer spending amid a rapidly increasing middle class and favourable business environments, will bolster Indonesian construction. East Kalimantan offers a substantial possibility for construction, particularly near the end of the projected period. However, downside risks to Indonesia’s short-term development are related with the global economy’s increasingly gloomy outlook amid intensifying US-China trade tensions, which could impact the construction sector.

Outlook for Malaysia

Closer to home, Oxford Economics expects that the Malaysian construction sector would remain subdued in the short term, despite the government’s revival of several large infrastructure projects including the East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) and LRT3. The sluggish property market, driven by a huge number of unsold private dwellings amid poor housing demand and excessive office vacancies, continues to push down construction investment. Nonetheless, Oxford Economics anticipates a surge in the second half of the projected period as excess capacity is gradually consumed despite fairly respectable economic growth. Furthermore, Malaysia’s favourable demographics will support long-term growth, notably in the housing sector.

Future Growth

According to Oxford Economics, growth will be concentrated in a small number of countries between 2020 and 2030. China will account for 26.1% of world growth on its own. India is predicted to account for 14.1% of global growth, while Indonesia is expected to account for 7.0%.

Global construction output is expected to be 35% higher in the next decade to 2030 than in the previous decade to 2020. In the decade to 2030, construction output is expected to total US$135 trillion.

Infrastructure is expected to be the fastest growing construction industry between now and 2030. Oxford Economics forecasts 5.1% annual growth in infrastructure construction output globally from 2020 to 2025, driven by record levels of government stimulus and the acceleration of pipelines of global mega infrastructure projects.